Critical Review of Rental Housing Scheme by MMRDA

From the desk of Vitasta Raina

Notes: The following was submitted as my Term Paper for US-613 "Urban Planning in India: Theory, Challenges and Approaches" April, 2019 Background and Policy

In the backdrop of severe housing shortages and rising slum populations in Mumbai, the Urban Development Department, State Government of Maharashtra issued Notifications for the implementation of the Rental Housing Scheme in Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) which aimed at provision of affordable housing on rental basis within the financial reach of the economically weaker sections in August 2008. With the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) as the Project Implementing Agency, these schemes were promoted as a ‘Vital Public Purpose’ and a ‘Slum Prevention Program’. The main objective of the Rental Housing Scheme was to provide 160 sq.ft. self-contained dwelling units on rental basis to the Economically Weaker section migrants to the Mumbai Metropolitan region. The rents were set at an affordable cost of Rs. 800 to 1500 per month.

The Rental Housing Schemes was envisaged as a Public- Private Partnership based on both the instrument of TDR and FSI as incentives capped at 4.00 to obtain the Rental Housing Free of cost. The developer will have to pay Infrastructure charges for development of infrastructure for the Rental Housing schemes to MMRDA. Subsequently, the state government lowered the highest FSI permissible under the scheme to 3.00. The size of the housing units was also increased to 320 sq.ft.

At inception, the Rental Housing Scheme seemed to capture the incoming migrants to the city before they find alternate routes into the vibrant informal rental economy of the city of Mumbai (slum clusters, goathans and Koliwadas), however, not only did the scheme fail in its intended objectives, it has created problematic enclaves within the MMR, where high-density housing with minimum basic infrastructure and limited social systems exist in isolation where low-income residents of the city are being allotted homes.

Development Models

The Rental Housing Scheme was to be developed under 3 primary models of development:

- TDR model- This model of development was to be undertaken by private developer with 3.00 FSI on private land in lieu of Land TDR of 1:1 and Construction TDR of 1: 1.33, where no in-situ development apart from Rental Housing was permitted with a 15% FSI to be applicable for convenient shopping by MMRDA, if desired. The Model was applicable in Municipal Corporation limits in the MMR including Greater Mumbai, Mira-Bhayander, Thane, Biwandi-Nizampur and Kalyan-Dombivali and in Special Planning Authority areas at Vasai-Virar, Badlapur, Kulgaon and Ambernath and in Panvel Municipal Council (later reclassified as corporation). The authority did not receive any Rental Housing project proposals under this model

- FSI Model- This model was applicable to U1 and U2 regions of the MMR, as well as the Municipal Coporation limits of Mira-Bhayander, Thane, Biwandi-Nizampur and Kalyan-Dombivali, Municipal Council limits of Karjat, Urban, Pen, Khopoli, Alibag and Panvel, and SPA areas Vasai-Virar, Badlapur, Kulgaon and Ambernath. Under this model, 4.00 FSI was granted for Rental Housing project on private land, where developer could build free sale housing on 3.00 FSI, and rental housing units with 1.00 FSI. The total project land was bifurcated into 75% for free sale housing and 25% for rental housing development. Further, 15% FSI of both rental housing component as well as Free Sale Housing could be used to construct convenient or commercial shopping. All the project proposals received by the Authority are under this model of development.

- MMRDA Land Model- In this model, applicable to lands vested with MMRDA anywhere within MMR, if MMRDA intends to develop the Rental Housing Scheme on land vested with it, then total FSI of 4.00 is granted. MMRDA may invite bids for construction rental housing tenements of 160 sq.ft. carpet area with 3.00 FSI from developers in lieu of 1.00 FSI with commercial use to be sold in open market. The authority did not receive any Rental Housing project proposals under this model.

- Housing Association Model- where a housing association would be formed which would be regulated by an independent regulator

- Arms-Length Management Organization (ALMO) model with an independent regulator

- Facilities Management Model where a contract would be given for property management of rental housing stock to a facility management company

Projects under the scheme

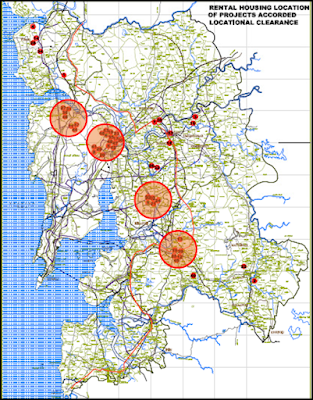

Since the year 2008, MMRDA granted Locational Clearance for 47 Rental Housing Scheme proposals with the potential of development of 61,946[1] Rental Housing Units. These projects are in various advanced stages of development and will be ready by December 2022. Out of these, 6 projects have been completed and handed over to respective ULBs- 1 in Mira-Bhayander Municipal Corporations with a total of 655 units, and 5 in Thane Municipal Corporation with combined 3,336 units; while 1 project has been allotted to tenants. It is noted that the schemes are clustered around four locations (refer Map below), with 15 projects in Thane Municipal Corporation, 13 in Mira Bhayander Municipal Corporation, 5 at Panvel Municipal Corporation and 6 at Palaspe Junction (at Panvel taluka).

|

| Map depicting Rental Housing Clusters. Source: MMRDA |

Of all the projects, 320 sq. ft. houses and shops are being constructed primary in U1 and U2 zones-under the jurisdiction of CIDCO-NAINA in villages Kon, Palaspe, Kolkhe and Raichur, and under the jurisdiction of MMRDA in villages Nilje and Ranjnoli in Thane district. These units total at 11,280 (including shops). Other locations where 320 sq. ft. units are being constructed is in Thane Municipal Corporation in 6 projects. Out of the total number of rental units proposed, 37,950 are 160 sq. ft. dwelling units (62%) while 23,142 are 320 sq. ft. units (38%). At present, apart from these 47 schemes, no new project is being considered under the rental/ affordable housing scheme.

Experience and Issues

In the initial phase of the Rental Housing Scheme, it fell into political trouble with the Shiv Sena with their leader Uddhav Thackery demanding that the policy be changed from providing rental housing to migrants coming into the MMR for employment to only migrants with a Maharashtra State domicile. This in effect cut out all low-income migrants coming into Mumbai region from other states in the country from benefiting from the scheme thereby subverting its principle goal as a “slum prevention programme”. Now, with the structural change in the policy, this goal has all but been forgotten.

Some of the initial issues with the policy were with regards to allotment and maintenance of the rental housing stock. While the policy had fleshed out the scheme in detail with regards to locational clearances, and building construction, post construction allotment of housing to eligible tenants as well as the overall maintenance of the housing stock created, and rent collection activities were not initially specified with much depth. This led to confusion regarding the stock created and several concepts for the same were floated. With the change in the status of the housing stock, these issues have now become redundant.

Another critical issue with the housing stock created was the fire safety of the buildings. While there was stated infrastructural provision for the stock mentioned in the policy, there were issues regarding fire safety from the fire department, as no clear provision was made for the same. Because of the high-rise, high-density structures, this proved to be a major issue. Other issues were with regards to multiple agencies involved in the clearance process. While the scheme was meant to be of ‘vital public purpose’ there was no single window clearance system. As a result, the MMRDA was responsible for the Locational Clearances of the project including looking at the overall schemes-whether the land area bifurcation (75-25) had been followed, whether there was an access road, and whether a transportation hub was in near vicinity of the project. The Building permissions including looking at land titles was left with the local authorities and various SPAs where the projects were located. Some of the issues because of this was:

- HDIL project at Vasai: While MMRDA had given Locational Clearance to the project, the project was stalled because the location chosen fell within CIDCO area where it had been zoned under “low density”. Because of this clash, the project which aimed at providing close to 2500 rental housing units never took off

- Land Title issue at TMC: In one project at Thane Municipal Corporation, a man filed a court complaint against MMRDA claiming that the Locational Clearance given to a rental housing scheme in TMC was illegal because there was ambiguity with the land title, and that the builder has illegally built the project on the land. This situation was brought on because in-depth land title checking was not under the purview of MMRDA despite being responsible for Locational Clearances and was left to be studied by the Local Authorities during the building permission process.

Current Status

In August, 2014, the Government has replaced the ‘Rental Housing Scheme’ by ‘Affordable Housing Scheme’. Under the new regulation, 50% of the housing stock created under the Rental Housing Scheme is to be allotted to textile mill workers on ownership basis, while the remaining 50% would be allotted on ownership basis as affordable housing. Further, the scheme discontinued rental housing in non-ULB areas (U1 and U2 Zones), and mandated that the scheme is permissible in ULB areas baring Greater Mumbai, Navi Mumbai and Matheran, only on “residential zone” plots where the proposed FSI is greater than 1 and where TDR is permissible. The minimum plot area for such schemes is 4000 sq. mts., excluding reservations.

The new scheme has retained some of the essential features of the rental housing scheme, with FSI capped at 3.00 with a 1:3 ratio between affordable units and free sale housing and 75%-25% bifurcation of land between free sale and affordable units respectively. The dwelling unit size has been increased to 25 sq. mts. (269 sq.ft.) except where 160 sq. ft. carpet area units have already been constructed. In terms of allotment, the scheme has mentioned that up to 25% of the units would be allotted free of cost to respective PAPs (Project Affected Persons) or as transit accommodation free of cost, 25% would be sold outright to State govt and statutory authorities as staff quarters, while the remaining 50% would be sold as affordable housing by MHADA.

Currently, under the new allotment policy, 111 affordable housing units have been allotted to class III and IV employees of MMRDA in District Thane, while 2477 units[2] in Kon village under the jurisdiction of NAINA developed by Lucina Land Development Limited has been allotted to mill workers.

The present allotment policy for affordable housing units as per information from MMRDA is as follows: 50% units in ULB areas for transit accommodation of PAPs, and 50% in non-ULB areas for mill workers, while the remaining 50% of both ULB and Non-ULB areas is distributed as tabulated below:

MMRDA Class 3 and 4 employees | 3% |

Other Govt. Class 3 and 4 employees | 10% |

Police Dept. Class 3 and 4 employees* | 10% |

PAPs of MMRDA/ULBs as required, or to be handed over to the ULBs for PMAY, or shall be utilized for other Central and State Level Housing Schemes | 77% |

Allotment of Affordable Housing Unit. Source: MMRDA

Conclusions

While ambitious Rental Housing Scheme initially began as a Slum Prevention Programme to provide shelter on rent to rural and urban migrants coming into the city for employment, thereby breaking the cycle of rent seeking in slum areas, where the new migrants could afford shelter, the scheme took a drastic turn, becoming an affordable housing policy that provided housing for class III and IV employees of various government organizations. It not only failed in its stated objectives, but also perpetuated the myth that housing in itself was only the provision of ‘house’. While on one hand it does try to provide affordable housing for lower income groups, it does nothing to prevent new slums from cropping up, and ignores the filtration system of housing leading to the creation of high-density ghettos in places where it is being built.

These locations, particularly in locations in U1 and U2 zones of the MMR, face inadequacy of physical infrastructure such as water supply, sewage connections and power supply, but also are locations where social infrastructures, required for ‘liveability’ are missing. The quality of life thus drops drastically, unlike in existing ULB areas where such factors as provision of schools, medical care facilities and small retail shopping and places of recreation are more readily available. However, even in municipalities like Thame Municipal Corporation and Mira-Bhayander Municipal Corporation, the high-density rental housing schemes have out a strain on existing systems, and in smaller local bodies, due to lack of capacity, the situation of infrastructure provision, both social and physical is no better than in the U1 and U2 zones. The size of the house provided under the scheme, at 160 sq. ft. and 320 sq. ft. is also inadequate, and by some measure smaller than the average unit sizes available in slums areas. In Mumbai slums, the average per capita space available is 29.38 sq. ft. (SRA, 2016). If we consider the average household size of 5, then residents in new rental housing units (160 sq. ft.) developed under the scheme is 32 sq. ft. per capita. According to the National Building Codes, the minimum area of a dwelling unit[3] is approximately 165 sq. ft.

While the smaller dwelling unit sizes were increased in later phases of the schemes when it was increased from 160 sq. ft. to 320 sq. ft., it does not fare any better in increasing the quality of life of its tenants. With a change in tenure, from rental basis to permanent occupancy, one needs to consider the larger impact of living in such spaces with little space, in locations far removed from city centres and with patchy infrastructure. In a manner of speaking, by allotting these units to specific income groups, the scheme inadvertently is creating islands of deprivation and perpetuating social segregation due to housing which thwarts the natural social interactions which occurs organically in cities. While there was a clear mandate to locate these units close to transportation hubs such as railway stations and bus-stops to enable the residents to make long distance commutes to their places of work, this system fails when the nature of the tenure changes from rental to permanent occupancy. With a rental system, such dormitory (sleeper) townships become stepping stones for the tenants to move into better accommodation with changing financial situations. However, with a permanent housing in these locations, the residents are forced to live in substandard housing and the forces of market delivery overtime creates several informal systems such as informal retail and service sectors (Dhobis, street food vendors) around these housing locations, furthering the segregation of the townships from middle- and higher-income groups. This system impacts the younger generation living in such high-density, small unit size housing with little mixing between income groups, as the quality of schools and playgrounds, and other recreational activities is limited.

Another clear drawback with the Rental Housing Scheme was the abrupt disruption it created in largely agrarian regions in the U1 and U2 zones of the MMR. Once the locational clearances were given for the proposed rental housing schemes, there was an increase in land speculation, particularly in regions such as Panvel, and land from farmers were bought out by builders. This led to an increase in haphazard building activity in the region on one hand, and on the other hand, it led to a loss of livelihood for the farmers who while being compensated for the land in the short-term, do not possess the necessary skills to integrate adequately into urban service sectors. This situation bears similarity to Gurgaon where farmland was bought out by builders for constructing gated enclaves which excluded the original settlers of the region and created urban ghettos (original goathan areas), where eventually informal job seekers sought accommodation. Such systems of ad-hoc urbanization without paying heed to the integration and security of livelihoods of the marginalized communities leads to creation of unsafe cities with sharp divisions drawn between income groups. However, in the long term, such experiences with the Rental Housing Schemes remains to be seen.

[1] Source: MMRDA (Primary Data Collection) Dated 12/4/2017

[2] Information by MMRDA dated 12/4/2017

Ramakrishna Nallathiga, a. G. (2016). MMRDA RENTAL HOUSING SCHEME: A CASE OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING . Shelter, Volume 17, No. 1, 10-16.

Sandeep Ashar, Average living space in Mumbai: Each resident has just 8 sq m to call own, The Indian Express, 10 May 2016. Online. Available at: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/average-living-space-in-mumbai-each-resident-has-just-8-sq-m-to-call-own-2792538/

Comments

Post a Comment